Australia is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, yet on average an Aboriginal child born today will still live for many years less than a non-Aboriginal child.Why is it important for rugby league to join the campaign to close this gap?

It’s very, very important. A lot of people can look at third world countries and feel this great need to help. While it’s also very important to help overseas, you only have to look at remote places in Australia with Indigenous populations and you’d think you were in the third world. Australia is so rich financially and has huge land resources. We should be able to help these people.

Rugby League is a great platform to create awareness. Within the Indigenous population there are literacy problems which create barriers. But if children can see a healthy example from a sporting role model, this can create awareness about eating properly and being active.

For an Indigenous person to look at footballers, especially Indigenous footballers, it sets goals. “If they can get there, why can’t I?” Most children are more inclined to listen to their sporting heroes – whether they’re Indigenous or not.

Many people are aware of the statistics that show that Aboriginal people still on average die more than a decade before other Australians. But statistics don’t tell us about the human impact. What has been the impact of the life expectancy gap on your family and friends?

For me, it’s been a huge impact and I only have to go back home to Tingha to see that. There’s huge issues with diabetes and heart problems in my community. In my family alone, my Nan, uncles, aunties, they’ve all had triple bi-passes. Obviously to a degree that’s genetic, but there’s still a big lack of education about health and how to live a healthy life.

Although that’s getting better. My family are getting better at going to the hospital for a check up. It’s still a very scary thought and very close to home, especially with my Mum. For as long as I can remember she’s suffered from a heart condition. Even a fit bloke like me could suffer!

Participation in sport has been identified as a key factor in improving the health and well being of young Aboriginal people. What part has rugby league played in your own health? How can it help other Aboriginal people improve their physical and mental health?

It’s helped me so much by being fit. It’s taken the pressure off. Even in the early days as a teenager, I had flutters in my chest and that used to scare me. It doesn’t come around as much now because of my fitness and lifestyle.

If people want to help it goes back to education – to tell them to eat right – and rugby league comes into that again. The Titans run a healthy lifestyles program where we go into schools and teach children and parents about eating right and being active and as a game the NRL has the Eat Well, Play Well, Stay Well program.

Group fitness is great and I’m happy to put my hand up to help. It’s great to concentrate on the little ones but Mum and Dad need education and help too.

Closing the Gap isn’t just about improving physical health, but also mental health. You’ve spoken about your own battle with depression and how in 2002 you attempted suicide. How did you overcome these problems? What advice would you give to young people who may have thought of suicide?

Things can be going alright in life physically, but not mentally. Back in 2002, I wasn’t enjoying life, which led me to start questioning everything about life. The advice I’d give most of all is that in life you have to enjoy what you do. You need to ensure you have that support around you and do the best you can.

You’ve cited former team mate David Peachey as an inspiration for your work on and off the field. How important are positive role models for young Aboriginal people?

It’s so important. For me, I grew up in a Christian family and so I had that grounding and those beliefs. When I met Peachey, he showed me there was more to life than just being back at home. He showed me there were people suffering from drinking problems, alcohol issues. I’d seen these things at home, but nothing like this. He showed me the ropes and said it was OK to go out to other communities and the main thing was to always be yourself. He said to me, “because you’re so grounded, you’re halfway there.”

It’s important to show your face in the community, but more to show who you are. People see you on tv and they like how you play footy and that you’re famous, but they don’t know the real you. So to make a difference it’s important to be yourself and just be real.

What would life have been like for Preston Campbell without rugby league?

It would be different! I know for sure I’d be back in Tingha, but doing a 9 to 5 job. I know it wouldn’t have worried me as long as I was living with my family, having a good job and supporting my family.

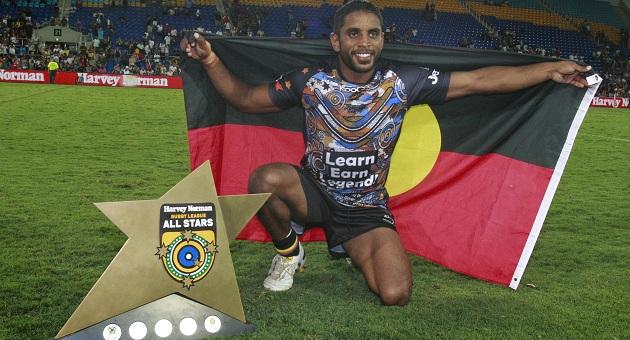

You’ve been the Dally M Player of the Year, captained the Indigenous All Stars team and won a premiership and the Ken Stephen medal. You’ve said that these achievements have given you a position where you can change things for the better. What are some of the things you’d like to change?

I’d like to change everything! But it’s taken me some time to learn that it’s not always possible. I’ve always wanted to do so much, but over time I’ve learnt to do the little things one at a time. I love working with children and trying to steer young ones in the right direction.

At only 75 kgs, Preston Campbell is one of the smallest and most courageous players in the history of the NRL. Originally from Tingha in northern New South Wales, Preston has played more than 200 games for the Gold Coast, Cronulla and Penrith. In 2001 he won the Dally M Player of the Year Award, and in 2008 the Ken Stephen Medal for community service. He was also the inaugural captain of the Indigenous All Stars representative team.