After years on the increase, food prices in Australia have recently been falling, according to New Limited analysis published on 7 January. Among the key factors, researchers cited the ‘nomalising’ of fruit prices after their sudden rise following natural disasters in Queensland and Victoria.

Sadly, this reassuring news came before the record heat wave claimed the lives of 10,000 sheep and cattle across New South Wales alone, and caused some stone fruit to literally cook on the trees.

While it’s too early to gauge the exact impact this latest extreme weather event will have on food markets, we can be certain that prices will not be staying down for long.

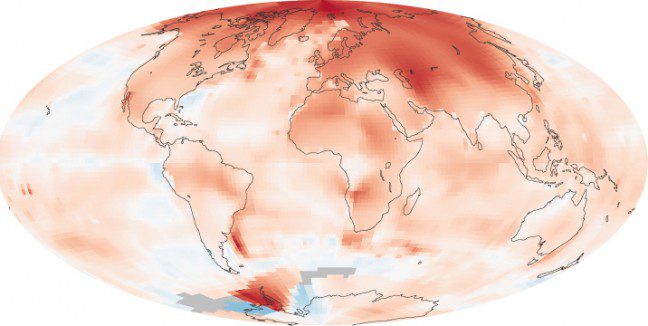

This is the reality in a warming world.

Slow changes in average temperature and shifts in rainfall patterns are causing yields in many regions throughout the world to decline. But the real hazard comes from the new weather extremes. In driving up temperatures, we are turbo-charging the climate and increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. Floods, tropical storms and heat waves can wipe out entire harvests in a stroke.

In the same week that Australia set a new record of 40.33 degrees Celsius for the national average maximum, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration confirmed that 2012 was the hottest year on record for the US.

Globally, November was the 333rd consecutive month of above average global temperatures. The occurrence of extremely hot events has risen by a factor of around 50, according to a paper published last year by NASA’s James Hansen and colleagues. The message from the Bureau of Meteorology has been unequivocal:

“The current heat wave – in terms of its duration, its intensity and its extent – is unprecedented in our records,” said David Jones in the Sydney Morning Herald on 9 January.

“Clearly the climate system is responding to the background warming trend. Everything that happens in the climate system now is taking place on a planet which is a degree hotter than it used to be.”

A hotter and more hostile climate is no longer a prediction. It is our new normal.

Australians are no strangers to extreme weather and the suffering it can bring. Heat waves in Australia reportedly harm more people than any other natural disaster.

But while climate change affects us all, it hits poor people in developing countries the hardest – ironically, those with the least responsibility for rising greenhouse emissions.

For those living on the edge, a sudden loss of livestock or a spike in global food markets such as followed the 2012 drought in the US can be a matter of life and death. Furthermore, communities may be unable to recover from one shock to the next. This cumulative impact can mean a downward spiral of worsening food security and deepening poverty.

Oxfam estimates that the price of key food staples, including wheat and rice, may double in the next 20 years – up to half of this increase caused by climate change. Predicted drought and flooding in southern Africa could increase the consumer price of maize and other grains by 120 per cent by 2030. Price spikes of this magnitude today would mean the cost of a 25kg bag of corn meal – a staple which feeds poor families across Africa for about two weeks – would rocket from around $18 to $40.

Australia has resources with which to bounce back from extreme weather disasters. Nonetheless, new research by The Climate Institute shows that the emotional and psychological toll from floods, heat waves and other traumas can linger for months, even years. Higher rates of drug and alcohol abuse, violence, family breakup, self harm and suicide are all apparent in the wake of these tragedies.

For poor countries, a hot world is a hungry world. For all countries, a hot world is a world of increased financial, psychological, emotional and other pressures.

Global temperatures are currently about 0.8 degrees above pre-industrial levels. The consequences of this are already stark. Contrary to some perceptions, there are no insurmountable technological or economic hurdles to keeping warming below two degrees – the widely accepted threshold for a safe climate.

All that is needed is political will and, to achieve that, public pressure.

Unfortunately, some further warming is inevitable, no matter how rapidly we manage to reduce emissions, and we have a responsibility to help vulnerable communities in poorer countries adapt.

Australia must meet its fair share of ongoing international climate finance – the promised funds to assist poorer countries with low carbon development and building resilience to the changing climate.

We’ve spent two decades squabbling over appropriate emissions reductions, carbon pricing, the safe number of parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere, and other technical matters.

It’s time we looked up from our calculators and balance sheets and recognised the human cost of a warming planet.

Dr Simon Bradshaw is Oxfam Australia’s climate change advisor